ISBN: –

Thomas Wijck's painted alchemists at the intersection of art, science, and practice

ISBN: –

Thomas Wijck's painted alchemists at the intersection of art, science, and practice

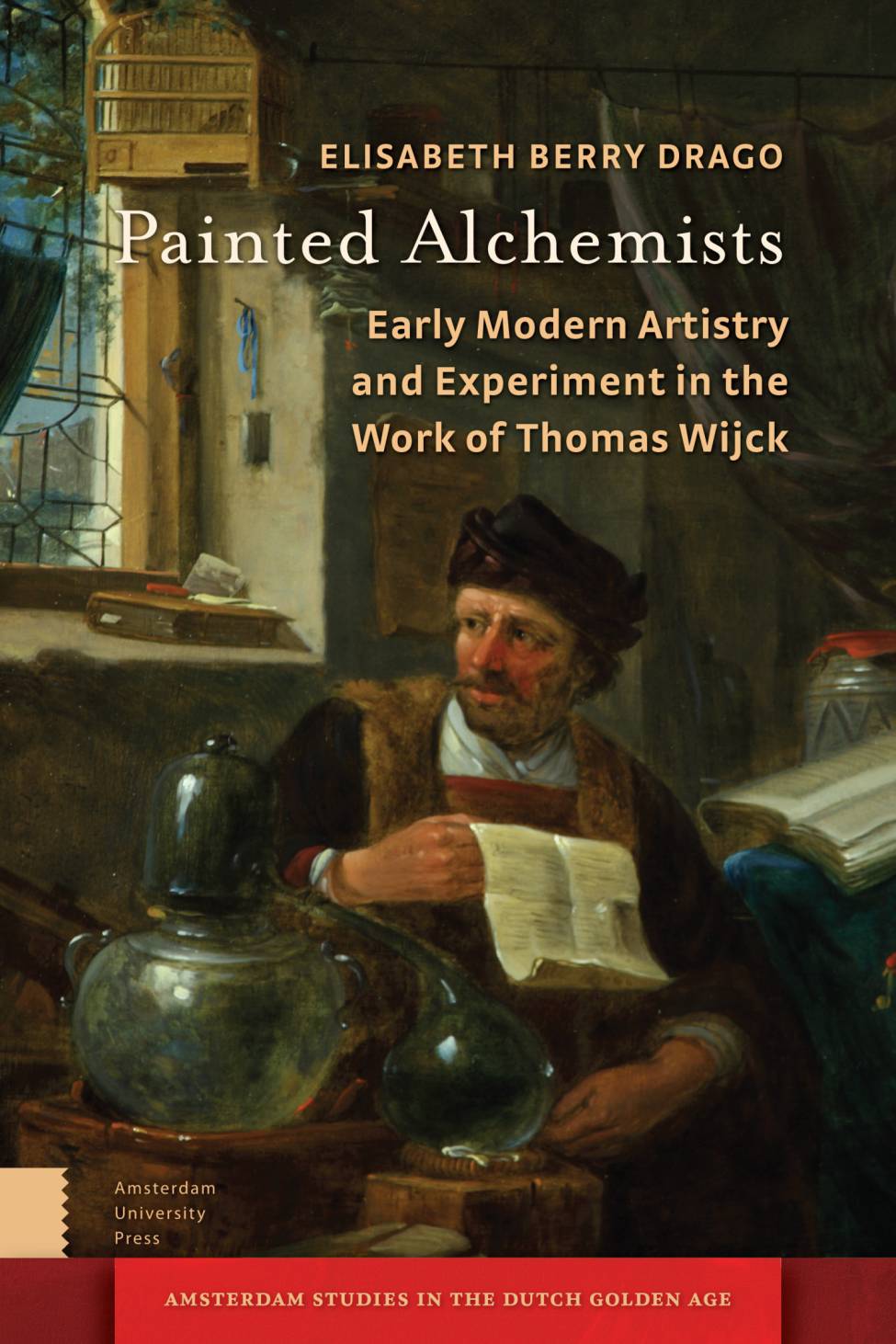

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries represent an alchemical “Golden Age,” a time of growth and discovery for alchemy’s diverse practitioners. During this era, alchemists were engaged in a wide array of commercial enterprises, from mining to dye and pigment manufacture to the production of chemical medicines. Alchemical treatises circulated across a broad spectrum of society, from artisans and tradesmen to scholars and princes. The term “laboratory” emerged during this period as a specific descriptor of sites of chemical inquiry—indicating alchemy’s importance to the history of science as a whole. Yet despite its past ubiquity and utility, alchemy has since borne negative associations with magic, occultism, delusion, and greed, and alchemical imagery has in turn suffered misinterpretation or obscurity. Many modern interpretations of alchemical art centralize Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1558 satirical print, The Alchemist, a scene that lampoons vain hopes for transmutated gold; others focus on the mess and disorder of the pictured workshop as signs of alchemy’s failures. Yet the popularity of alchemical scenes swelled during this period, particularly in the Dutch Republic, where they were produced in large numbers. The diversity of these images indicate a similarly diverse range of responses to alchemy, ranging from skepticism to respect, delight and curiosity. The alchemical paintings of Thomas Wijck (1616-1677) present a substantial body of laboratory imagery—as well as a remarkable challenge to narratives of greed and folly. Wijck’s painted laboratories model domestic harmony, scholarly study, and expert knowledge of materials. Rather than charlatans or dupes, his alchemists are respectable and scholarly artisans who pursue intellectual and empirical work. In representing alchemists as artisans, Wijck reframes alchemy in the context of the familiar, as well as socially and economically vital, artisanal workshop. His images further emphasize the practices and products of the laboratory, presenting colored powders and raw materials that epitomize the desirable and useful alchemically created pigments, dyes, and medicines that circulated widely in the early modern marketplace. Wijck’s choice to depict his alchemists as makers of artists’ materials, rather than seekers of gold or cures, is a remarkable one. It affirms the connections between his subject matter, his practices as a painter, and his place within a Netherlandish art-theoretical tradition that linked alchemy and experiment to artistic virtuosity. Wijck’s international success, and his connections to elite communities engaged in natural philosophical experiments, shed new light on the market for alchemical pictures and other “modern” genre scenes of emerging empirical disciplines. His specialization in alchemy further indicates its utility as a tool for fashioning an artistic identity rooted in curiosity, ingenuity, and transformation. As a painter, and particularly as a painter in oils, Wijck was connected to a legacy of experiment in workshop process, as well as concerns for mimesis, naturalism, and material change. The work of artists, like the work of alchemists, contained intellectual-creative and manual-material aspects. While the work of alchemists and painters might be considered artisanal, both alchemists and artists claimed a special status owing to their creative powers. Alchemy shared deeper connections (and rivalries) with art-making, centering on the replication of nature. Wijck’s formation of an artistic and professional identity around alchemical themes indicates his desire to explore this curious territory, and ultimately to demonstrate art’s superior claims to knowledge of the natural world.

Pages 330-459 missing from PDF. "All images removed due to copyright"--p. 329.